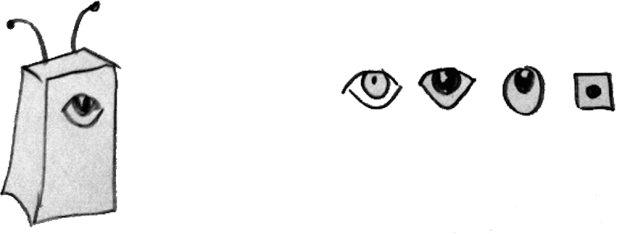

I recently added eyeballs, eyelids, eyelashes, and eyebrows to the wiglet genome, with various breed-able, evolvable attributes associated with them. Here’s a video showing one character with these extra ocular capabilities.

evolution

Podcast with Jeffrey Ventrella – on the Versatilist

Hey wiggy peeps,

I was recently interviewed on the Versatilist Podcast, by Patrick O’Shea.

http://versatilist.podomatic.com/entry/2016-10-03T08_42_23-07_00

In this podcast, Patrick and I kick around lots of ideas on artificial life, artificial intelligence, and augmented reality. I describe my ongoing efforts to develop a kind of self-animated character that can thrive in our highly augmented future.

Biodiversity, Big Numbers, and Worldly Wiglets

Let’s build an animal.

We’ll start simple, and gradually make it more complex. We’ll start with three “genes”. In this context, a gene simply means a number that determines a distinct physical quality of a thing (such as the width, height, or depth of a box):

Now let’s make another gene that determines roundness (like, rounding off the corners)…

The roundness of this simple animal ranges from min to max, with max being totally spherical (or ovoid, depending on what the other genes are set to). Now we have four genes. Let’s imagine that each gene has four degrees of value. So, in the case of the roundness gene, that means roundness can be 0.0, 0.333, 0.666, or 1.0. That’s four evenly-spaced degrees of roundness. So, with four genes, each having four degrees of influence, we can do the math. We conclude that the variety of animals is four raised to the power of four (4*4*4*4 = 256). That’s two hundred fifty six unique kinds of animals. Some of them may be very similar to each other, but they are still each different in terms of tallness, fatness, depth, and roundness.

And we haven’t even added the eyes yet. Let’s do that. And while we’re at it, let’s add some antennae.

We can create some variety of eye shape, size, color, etc. We can even have a gene for number of eyes. If that had four values, we can say the number of eyes can be 0, 1, 2, or 3. Of course we need to have a gene to determine how wide apart the eyes are, etc. The antennae can have genes for length, amount of separation, floppiness, etc. I can imagine that with these features and their variations, we could easily end up with about ten genes.

What’s 4 raised to the power of 10?

Oh, not much (yawn). Just… 1,048,576. That’s a little over a million.

Now, consider wiglets:

The wiglet genome has 1000 genes, and each gene can have 256 degrees of influence. What’s 256 raised to the power of 1000?

Answer:

173 766 203 193 809 456 599 982 445 949 435 627 061 939 786 100 117 250 547 173 286 503 262 376 022 458 008 465 094 333 630 120 854 338 003 194 362 163 007 597 987 225 472 483 598 640 843 335 685 441 710 193 966 274 131 338 557 192 586 399 006 789 292 714 554 767 500 194 796 127 964 596 906 605 976 605 873 665 859 580 600 161 998 556 511 368 530 960 400 907 199 253 450 604 168 622 770 350 228 527 124 626 728 538 626 805 418 833 470 107 651 091 641 919 900 725 415 994 689 920 112 219 170 907 023 561 354 484 047 025 713 734 651 608 777 544 579 846 111 001 059 482 132 180 956 689 444 108 315 785 401 642 188 044 178 788 629 853 592 228 467 331 730 519 810 763 559 577 944 882 016 286 493 908 631 503 101 121 166 109 571 682 295 769 470 379 514 531 105 239 965 209 245 314 082 665 518 579 335 511 291 525 230 373 316 486 697 786 532 335 206 274 149 240 813 489 201 828 773 854 353 041 855 598 709 390 675 430 960 381 072 270 432 383 913 542 702 130 202 430 186 637 321 862 331 068 861 776 780 211 082 856 984 506 050 024 895 394 320 139 435 868 484 643 843 368 002 496 089 956 046 419 964 019 877 586 845 530 207 748 994 394 501 505 588 146 979 082 629 871 366 088 121 763 790 555 364 513 243 984 244 004 147 636 040 219 136 443 410 377 798 011 608 722 717 131 323 621 700 159 335 786 445 601 947 601 694 025 107 888 293 017 058 178 562 647 175 461 026 384 343 438 874 861 406 516 767 158 373 279 032 321 096 262 126 551 620 255 666 605 185 789 463 207 944 391 905 756 886 829 667 520 553 014 724 372 245 300 878 786 091 700 563 444 079 107 099 009 003 380 230 356 461 989 260 377 273 986 023 281 444 076 082 783 406 824 471 703 499 844 642 915 587 790 146 384 758 051 663 547 775 336 021 829 171 033 411 043 796 977 042 190 519 657 861 762 804 226 147 480 755 555 085 278 062 866 268 677 842 432 851 421 790 544 407 006 581 148 631 979 148 571 299 417 963 950 579 210 719 961 422 405 768 071 335 213 324 842 709 316 205 032 078 384 168 750 091 017 964 584 060 285 240 107 161 561 019 930 505 687 950 233 196 051 962 261 970 932 008 838 279 760 834 318 101 044 311 710 769 457 048 672 103 958 655 016 388 894 770 892 065 267 451 228 938 951 370 237 422 841 366 052 736 174 160 431 593 023 473 217 066 764 172 949 768 821 843 606 479 073 866 252 864 377 064 398 085 101 223 216 558 344 281 956 767 163 876 579 889 759 124 956 035 672 317 578 122 141 070 933 058 555 310 274 598 884 089 982 879 647 974 020 264 495 921 703 064 439 532 898 207 943 134 374 576 254 840 272 047 075 633 856 749 514 044 298 135 927 611 328 433 323 640 657 533 550 512 376 900 773 273 703 275 329 924 651 465 759 145 114 579 174 356 770 593 439 987 135 755 889 403 613 364 529 029 604 049 868 233 807 295 134 382 284 730 745 937 309 910 703 657 676 103 447 124 097 631 074 153 287 120 040 247 837 143 656 624 045 055 614 076 111 832 245 239 612 708 339 272 798 262 887 437 416 818 440 064 925 049 838 443 370 805 645 609 424 314 780 108 030 016 683 461 562 597 569 371 539 974 003 402 697 903 023 830 108 053 034 645 133 078 208 043 917 492 087 248 958 344 081 026 378 788 915 528 519 967 248 989 338 592 027 124 423 914 083 391 771 884 524 464 968 645 052 058 218 151 010 508 471 258 285 907 685 355 807 229 880 747 677 634 789 376.

That’s the total number of unique combinations of 1000 byte-sized values. All that variety is held in one kilobyte of data.

Now, to be sure, 256 is a pretty high resolution when you’re talking about things like nose length, or the amount of redness in skin color. Our eyes would not be able to pick up the subtle difference between a redness of 134 vs. a redness of 135. But even if we were to make each gene have only four degrees of influence, we would still have a large number. And also, wiglet evolution is not done yet. The wiglet genome is only using about 200 of its genes. The rest haven’t been determined yet :) So, to be more realistic, let’s calculate four raised to the power of 200:

2 582 249 878 086 908 589 655 919 172 003 011 874 329 705 792 829 223 512 830 659 356 540 647 622 016 841 194 629 645 353 280 137 831 435 903 171 972 747 493 376

That’s much better. That’s only, um…. Gosh…that’s still a big number!

Now consider real-world animals:

We share many of the same genes as these animals. And so theoretically we might be able to build mathematical models that describe our differences.

To be sure: real-world genes are vastly more complicated than the simple bytes that determine wiglet biodiversity. In any case, you can imagine that if we were able to do some mathematical estimate on the amount of variety in these animals, we would have something much larger than the huge number above.

The Exponential Nature of Biodiversity

The point of all this is not to show how big we can make a number. It is to emphasize the amazing variety that is possible on this planet. Evolution has taken trillions of experimental turns and twists over the 3+ billion years of life on Earth. We are only seeing a sliver of the possible variety that could have come about if, say, the sun were a little closer, or if there had never been a catastrophe that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Biodiversity is synonymous with the health of the planet. The collective of all ecosystems relies on genetic variety for its resilience.

Wiglets can serve as an illustration (a simple one but still potentially useful) for the biodiversity that constitutes the health of our planet. Our new augmented reality book (Peck Peck’s Journey) shows only a handful of the kinds of characters that the wiglet genome can produce.

But there’s a lot more in store. The Wiglet Hatchery (forthcoming) will allow users to breed wiglets and distribute them around the world. Stay tuned for the Wiglet Hatchery – coming at the end of 2015.

Now, if we could only get a few trillion users to purchase our apps, we’d be in good shape :)

We’ll get there. One gene at a time.

-Jeffrey

Mind Children for Children’s Minds

Hans Moravec wrote a book in 1990 called Mind Children, about robots and the future of humans and artificial intelligence. I haven’t read the book, but I did read Moravec’s “Human Culture: A Genetic Takeover Underway“, which influenced me greatly. I included it as required reading for an Artificial Life class I taught at Tufts in the 90’s.

As we approach the singularity, it will become increasingly evident that Darwinian evolution will have minimal effect as technological evolution races forward at ever-increasing speeds, leaving human genetic evolution in the dust. In a way, you could say that human evolution is indeed happening right now at a very high rate (that is, if you replace the ancient agents of replication (genes) with the more nimble agents of replication (memes)…and the emergent manifestation of interacting memes: human culture – and technology.

…which leads me to why I used Moravec’s book title in the title of this blog post. Currently, children have more than good old-fashioned cartoon characters and plastic dolls to play with. Their toys are coming to life.

When you add augmented reality with artificial intelligence, a new kind of animated personality begins to emerge.

Real and imaginary are about to enter into a future dance in which they will whirl at such a velocity that we may have a hard time telling them apart.

But what are the consequences of animated characters that become more “alive” than ever before? Children are more prone to failing the Turing Test. So…will more realistic AI characters confuse their developing theories of mind?

Some argue that this is mostly positive; it simply fuels a child’s imagination, which already naturally blends real and imaginary as a matter of course.

The picture below is from an article titled: Neuroscientists identify brain mechanisms that predict generosity in children.

This kind of research is being used by some toy manufacturers and game designers to teach kids social skills.

Let me just state an opinion, for the record:

If you want kids to learn how to socialize, there is no substitute for playing with REAL kids.

(A possible exception may be autistic kids who need tools to give them some non-face time to give them some training for the real thing.)

Now, why would I state that kids need to play with each other to learn to socialize, while at the same time eagerly developing self-animated characters in augmented reality?

I believe the key is in the intent.

The way we must bravely enter into our technological future and to prepare that future for our children is to keep a clear distinction between real and imaginary – to stay on top of the game, as it were. And to give kids the tools to enhance their imaginations – while not distorting their sense of reality. This may become a challenge as screen-time and face-time blur with ever convincing digitally-enhanced experiences. But it is important to keep in mind.

We need to keep the problem of “robot morality” in the same bucket as age-old problems of how kids react sympathetically to cartoon characters.

That’s my opinion. What’s yours?

-Jeffrey